Spending last week in New Orleans, at the Hartford Nursing and Social Work preconference meetings followed by the meetings of the Gerontological Society of America, was truly exciting and stimulating. Not only is the cutting edge science I saw very promising for the future, but also the ever-growing cadre of excellent people the Foundation has been privileged to support promises that we will have the leaders we need to turn that evidence into action. The need for action is, however, sadly getting clearer--as is often the case, things may have to get worse before they get better. So, first the bad news and then the good.

In the last two weeks, two major reports have been released documenting the poor quality of health care for older adults. They translate into wasteful spending by the Medicare trust fund and worse, preventable suffering and death. First AHRQ (The Federal Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality) came out with an analysis of preventable hospitalizations in the US. They found that 10% of all hospitalizations in the US are preventable, meaning that they are due to acute or chronic conditions that ought to be controlled by adequate ambulatory care. Sounds bad? It gets worse–60% of those four million preventable hospitalizations are among the 13% of Americans who are 65 years old or more. These are the people who all HAVE insurance. Yet our delivery system is simply unable to provide them with prevention-oriented, responsive, comprehensive, guideline-level care.

The other shoe to drop was the report of the Office of the Inspector General (OIG) of Health and Human Services on the rate of adverse events among hospitalized Medicare beneficiaries. According to this study, 14% of hospitalized beneficiaries experienced an adverse event (e.g., delirium, pressure sore, infection, or medication error–the routine, well-documented hazards of hospitalization for older people) that was likely preventable. (Another 13% of beneficiaries experienced an adverse event that was ruled not likely to have been preventable.) Worse, the severity of harm was such that the OIG estimated that 1.5% of all hospitalized patients actually died at least partly due to such an adverse event. That percentage might sound low, but in real numbers, that’s 15,000 a month and 180,000 a year. Donald Berwick, MD, Administrator of CMS, and Carolyn Clancy, MD, Director of AHRQ, both concur with the findings of the OIG in their letters of response to the report. Dr. Clancy writes, “The findings in the report are consistent with prior studies but are nonetheless disturbing.”

Doing the math makes me sad. Looking at the 2.4 million preventable hospitalizations, 36,000 older adults will die at least partly because of an adverse event in the hospital–where they shouldn’t have been in the first place.

Doing the math makes me sad. Looking at the 2.4 million preventable hospitalizations, 36,000 older adults will die at least partly because of an adverse event in the hospital–where they shouldn’t have been in the first place.

So what are we doing about it? I am pleased to say there are very transformative things going on. In just one session at GSA, “Re-Forming Health Care: Models to Integrate Evidence, Practice and Policy for Delivery System Reform,” I was privileged to introduce three JAHF grantees who are creating the tools we need to change health care for the better. Nancy Whitelaw, PhD, director of NCOA’s Center for Healthy Aging; Eric Coleman, MD, director of the Practice Change Fellows Program (among other jobs); and Steven Dawson, president of PHI, the Paraprofessional Healthcare Institute.

As I’ve written before, while we have a great engine of health care change in drug and device research, in the rest of health care we have lacked the fundamental infrastructure of change and quality improvement. These three talks provided at least three key tools for the change we need.

Dr. Whitelaw’s work promotes evidence-based health promotion programs that can be delivered through community agencies. She creates an efficient infrastructure through which we can provide quality ambulatory care that can prevent illness and promote health, based on sound evidence, rather than custom or convenience. If one of the fundamental tasks of health reform is to re-orient the system towards health promotion and not just treatment of disease, Dr. Whitelaw’s work is essential. [{filedir_6}images/wp-content/uploads/2010/11/101123-GSA-Whitelaw-2010.pptx

Dr. Whitelaw’s work promotes evidence-based health promotion programs that can be delivered through community agencies. She creates an efficient infrastructure through which we can provide quality ambulatory care that can prevent illness and promote health, based on sound evidence, rather than custom or convenience. If one of the fundamental tasks of health reform is to re-orient the system towards health promotion and not just treatment of disease, Dr. Whitelaw’s work is essential. [{filedir_6}images/wp-content/uploads/2010/11/101123-GSA-Whitelaw-2010.pptx

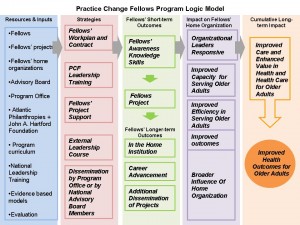

Dr. Coleman’s Practice Change Fellows (PCF) program provides another key ingredient for system change: leadership. At the Hartford Foundation we believe that effective and skilled leadership is essential for the kind of complex redesign needed in health care. Too many health care administrators and practitioners assume that the current organization of delivery is the way it has to be. They give far too little attention to innovation in health care design, staffing, and organization. On the other hand, clinical leaders who understand what does not work in the current system often lack the skills needed to lead change through a maze of business, communications, and managerial obstacles. The PCF program helps develop leaders who can navigate this maze and build the delivery system we need in the future.

Dr. Coleman’s Practice Change Fellows (PCF) program provides another key ingredient for system change: leadership. At the Hartford Foundation we believe that effective and skilled leadership is essential for the kind of complex redesign needed in health care. Too many health care administrators and practitioners assume that the current organization of delivery is the way it has to be. They give far too little attention to innovation in health care design, staffing, and organization. On the other hand, clinical leaders who understand what does not work in the current system often lack the skills needed to lead change through a maze of business, communications, and managerial obstacles. The PCF program helps develop leaders who can navigate this maze and build the delivery system we need in the future.

And finally, Mr. Dawson’s work at PHI on the coaching approach is the final ingredient for transformation. Developed originally as a way of supporting and engaging direct care workers to do their best work in a respectful work environment, PHI has found that the coaching approach is central to organizational change management in health care. The coaching approach incorporates a commitment to quality work while treating the workforce in an empowering way that ultimately leads to more person-centered and higher quality care. By enabling workers to do the best they can, it helps whole organizations live up to their best aspirations.

And finally, Mr. Dawson’s work at PHI on the coaching approach is the final ingredient for transformation. Developed originally as a way of supporting and engaging direct care workers to do their best work in a respectful work environment, PHI has found that the coaching approach is central to organizational change management in health care. The coaching approach incorporates a commitment to quality work while treating the workforce in an empowering way that ultimately leads to more person-centered and higher quality care. By enabling workers to do the best they can, it helps whole organizations live up to their best aspirations.

I could not be prouder that the Foundation has been able to support these great leaders and their vital contributions. I also thank GSA for making these and the many other inspiring presentations I saw last week possible. There are many great ideas and great people in geriatrics—we just need to introduce them to the broader health care audience.