Janice Lynch Schuster works with Joanne Lynn, a geriatrician and friend of the Hartford Foundation, at the Center for Eldercare and Advanced Illness at the Altarum Institute, a new voice in the field of aging and end of life issues. Learn more about the Center's work at www.medicaring.org, or follow them on Twitter @medicaring. Health AGEnda is delighted that Janice answered our call for guest posts in last week’s blog.

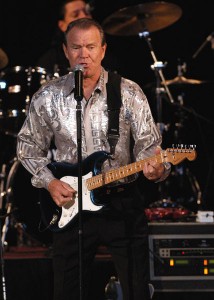

When I was a little girl, country singer Glen Campbell had a variety show on television called “The Glen Campbell Good Time Hour.” As I remember it, it was a good time; in my young imagination, I often confused him with my father, who I thought was just as handsome and talented and fun as Glen. I loved his songs and wanted to learn to play guitar so I could be more like him.

When I was a little girl, country singer Glen Campbell had a variety show on television called “The Glen Campbell Good Time Hour.” As I remember it, it was a good time; in my young imagination, I often confused him with my father, who I thought was just as handsome and talented and fun as Glen. I loved his songs and wanted to learn to play guitar so I could be more like him.

Sadly, Mr. Campbell has been diagnosed with Alzheimer’ disease. As most people know, Alzheimer’s is the primary cause of dementia, a gradual loss of brain function that becomes more common as we age. As the disease slowly and insidiously strips us of our thoughts and memories, it strips us of our lives and torments our loved ones in a grim process that can take years to unfold. Mr. Campbell’s decision to put a face on this awful disease by continuing to tour is a mark of real courage and heart. I don’t know how long he’ll last on the road—and early reviews, pre-diagnosis, panned him for being so forgetful and bumbling—but I hope that road takes him into some kind of good night, Rhinestone Cowboy.

Not many celebrities let us come so close. In our wild pop culture pursuit of public figures, we are eager to hear the details of their private lives—we buy up People and Star and Us by the ream. We want to know who’s pregnant, who’s with whom, who’s sleeping where, who’s in rehab, and who’s out. We want to hear about celebrities’ brave battles against one illness or another—bipolar disease or addiction, cancer or diabetes. We are thrilled when a gaunt but apparently cured Michael Douglas emerges from chemotherapy. We are sad when Patrick Swayze falls to pancreatic cancer. And we cry when Clarence Clemmons succumbs to a stroke. We collectively mourn the deaths each week of various celebrities whose lives, we think, touched our own.

But we don’t really want to know the details of stars’ final months and days. Christopher Hitchens’ extraordinary essays in Vanity Fair notwithstanding, we don’t want to hear public stories of what it’s like to live with—and die of—a chronic, serious illness. We want stories that are about youth and beauty—or, at the very least, stories that wrap things up in a comfortable ending. It would make us too sad, too lonely, too mortal to hear more about what is likely in store for each of us: Months or years living with a disease that will prove fatal. I worry that we aren’t able to tell these stories, or bear witness to them, or acknowledge the long and difficult journey that is, in fact, in store for most of us.

Absent such public telling of deeply private moments, we have no cultural framework from which to think about what it means to live with a bad disease for a long time. For the most part, the stories we see on television or at the movies are full of sudden and violent death, or conclude after a compact two-hour drama with sweet deathbed scenes in which everyone says goodbye and the eyes close. For most of us, it’s not going to be like that: We will instead live for many years with chronic and debilitating conditions that will render us increasingly dependent on others for our care.

Without stories of the reality of chronic illness to draw upon, we wind up stuck in our death panel absurdities and our assisted-suicide debates. We reach a time when a loved one is suffering from a serious illness and we throw up our hands because we haven’t a clue what to do. We have no images or stories or collective narrative from which to draw. And so we end up enduring one of the most difficult of life’s transitions alone, and making it up as we go along. Too many of us, patients and families, find ourselves isolated and frightened, abandoned by our communities.

When I tell people about my work writing about what happens at the end of life, they inevitably tell me their stories about their mothers and fathers, their grandparents and extended family. They talk about how lucky they were to have good pain control, or how horrifying it was to listen to a loved one struggle to breathe. They describe their uncertainty and their fear. What a difference such shared stories might make for people facing the end of life. Such stories might give us a way to navigate these profoundly private transitions while understanding that we are not alone in the journey. They might give us a platform from which to discuss larger and more important issues of society and culture, of how we will care for one another as millions of us grow old together.

Watching Glen Campbell tour might not be the best story of the year, but it will certainly be among the most poignant. It may be excruciating for his family and friends, but it may also give the rest of us some insight into what we face and some sense of the kinds of policies and social constructs that we need to navigate this new territory. I hope, for Mr. Campbell’s sake, that the Rhinestone Cowboy finds peace and relief from his suffering. In the meantime, I hope the rest of us learn how to talk about the end of life, and talk with purpose and meaning and real understanding. Once we start that conversation, we might find ways to construct programs and policies that support us through the difficult passages we all will face.