If you can stay calm while others all about you lose their heads, sometimes it means you just don’t understand the problem.

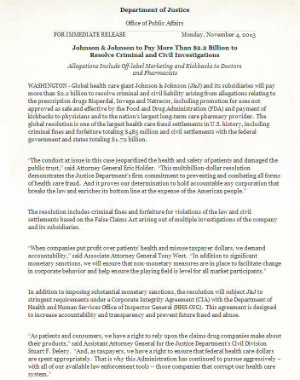

Click on document to read the full Department of Justice press release.

Click on document to read the full Department of Justice press release.Most of the time, being reasonable and understanding and putting yourself in the other fellow’s shoes is the right thing to do. But sometimes being reasonable and understanding just supports an unjust status quo, reduces any sense of urgency to action, and makes one complicit.

Unfortunately, in the moment, it is very hard to tell what kind of situation you are facing.

This is the ambivalence I’ve felt about the rampant use of antipsychotic drugs in long-term care—is it the result of good people doing their best in daunting circumstances who therefore deserve our help or is it a spreading evil that deserves nothing but condemnation?

Yesterday’s announcement of a record-breaking $2.2 billion settlement by Johnson and Johnson and its subsidiaries to resolve allegations by the U.S. Department of Justice of improper marketing efforts of drugs including Risperdal, a leading antipsychotic, brings clarity.

As part of this agreement, according to a Justice Department statement, Janssen (a Johnson and Johnson subsidiary) admitted that it promoted Risperdal to health care providers for treatment of psychotic symptoms and associated behavioral disturbances exhibited by elderly, non-schizophrenic dementia patients—an off-label use. These improper marketing tactics allegedly included kickbacks to long-term care pharmacies for encouraging the use of the atypical antipsychotic in nursing home patients.

As part of the settlement, Johnson and Johnson is entering into a Corporate Integrity Agreement that will subject many of its corporate practices to supervision by the Office of the Inspector General of the Department of Health and Human Services.

In light of these revelations, some context and recent history may be useful. On the one hand, the behavioral symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease (in addition to the cognitive impairment itself) can be hard to take for family caregivers and professionals alike. I recall one resident in the Special Care Unit at the Philadelphia Geriatric Center where I worked who could no longer talk, but would follow staff around and just scream all day long. Others would try to escape the secure unit and potentially put themselves at risk.

More broadly, some people with dementia can hurt themselves or others. Routine events like baths/showers can be causes of disagreement and even physical conflict between people with dementia and their caregivers.

Some large share of these problem behaviors can be addressed by behavioral interventions such as redirecting, more person-centered care, and the complex of institutional transformation called “culture change.”

Our grantees at PHI have worked for years in this area to help front-line nursing assistants get training and skills in caring for people with dementia The John A. Hartford Foundation’s new leader of its Change AGEnts initiative, Laura Gitlin, and her collaborators have called attention to these approaches in their JAMA article Managing Behavioral Symptoms in Dementia Using Nonpharmacologic Approaches: An Overview. They also have made available a MOOC (Massive Open Online Course) on the issue.

On the other hand, these non-pharmaceutical approaches to disturbing behavior in long-term care are staff intensive (read expensive) and uncertain (read hard to implement without organizational commitment—see also expensive). And while the accounting is very complicated, we don’t pay long-term care facilities terribly well for their services, and certainly not their front-line workers.

So despite an enormous victory for nursing home reform in OBRA ’87—which tried to minimize the use of physical and “chemical restraints” in long-term care, except under very limited conditions—we all seem to have slipped badly and without much notice into dangerous habits.

According to JAMA, in 2012 the rate of “off-label” prescribing of antipsychotic drugs to nursing home residents for the control of dementia-related behavioral problems was 23.9 percent—almost a quarter of long-stay nursing home residents. And much of this prescribing was for newer, atypical antipsychotic drugs that—while no more appropriate than older medications—were both very expensive and associated with higher rates of death. This frequent use of antipsychotics (both typical and atypical) comes in the face of “black box” FDA warnings, required monthly consulting pharmacist review of medication usage, and a nursing home regulatory system that is said to be so strict as to only be rivaled by the nuclear power industry.

Trying to be helpful, in March of 2012 the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) kicked off a voluntary “National Campaign” to reduce antipsychotic use by 15 percent by the end of 2012 (i.e., from 23.9 percent to 20.4 percent) and even further in 2013.

Former American Geriatrics Society president and LeadingAGE policy VP Cheryl Phillips has created a slide presentation on the issue. You can also watch the kickoff webcast for the CMS “Campaign” for the reduction of antipsychotic drugs, featuring national long-term care leaders and closed by our own Alice Bonner, an alumna of the Practice Change Fellows program who was working for CMS at the time.

Unfortunately, as reported in JAMA in September, the effort missed its initial goal (only reducing national rates to 21.7 percent by first quarter 2013 and seems to have been OTE (overtaken by events) in Washington in the past few months, causing it to fall off the list of CMS priorities.

Perhaps the breaking news about the J&J settlement will finally make a difference. Perhaps CMS (and I) misunderstood the problem. Perhaps it wasn’t a case of good people faced with difficult situations who needed coaching, but rather a case of deliberate of malfeasance requiring punishment.

Perhaps the heroes in the case are actually the whistleblowers around the country whose lawsuits brought under the False Claims Act initiated the DoJ action and who will get about $165 million from the settlement. I know we will learn more about this story over time (but probably not all, now that the case is being settled), but it looks to me that this situation was better addressed with confrontation and denunciation than understanding and assistance. Only time will tell for sure.