Record numbers of people are crossing the threshold into old age, and many are living well into their 80s and 90s. New medical procedures and drugs become available every day, and quality of care and of life in the weeks and months before death is becoming a more common topic in professional and popular literature. Questions abound related to the use of invasive technology to extend life when the burden of treatment is great, and whether it is appropriate to “do something ” just because something can be done.

While physicians, lawyers and ethicists express varied points of view, the voice most needed is sometimes the least heard--that of the individual. What happens when a patient’s wishes are not known and he is unable to participate in making decisions? The default response is too often to use everything the system has to offer: intensive care, aggressive surgical procedures, medications, and life-sustaining support. It’s a costly policy in both dollars and human resources. And it may well be exactly the opposite of what the patient would have wanted. So how do we avoid the default response?

The answer, of course, is to ask the sick, frail, or older person—while still conscious and lucid—what sort of treatment he or she might want near life’s end. This seems simple at first consideration, but can often be difficult. Many physicians and health providers are simply not comfortable or skilled in initiating these conversations. And even if you get cogent answers, what sort of legal weight do they bear? How do you write down the answers and make sure that they get to the next person? Should a patient declare he or she wants a DNR (a do-not-resuscitate order), can a hospital, physician, or nurse be sued by family members for following the order? And how can you guarantee that wishes would be followed?

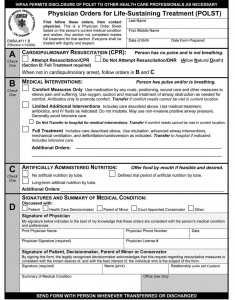

In eleven states, the answer is the Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment (POLST) paradigm, developed in Oregon in 1991. The POLST mission is to ensure that a seriously ill person's wishes regarding life-sustaining treatments are known, communicated, and honored across all health care settings. That means helping the patient communicate his or her wishes effectively, documenting the resulting medical orders on a bright pink, easily recognized form signed by the primary care physician, and getting a promise from health care professionals to honor these wishes.

POLST is an excellent tool for patients and families. It engages the individual in the decision-making process and, when used with an advance directive that names a proxy health-care decision maker, it helps ensure that care is provided based on the wishes of the person, including limiting care like intensive care unit stays or intubation. This protects against pointless suffering, and allows patients to know their wishes will be honored, even if they can’t personally enforce them. It also helps both patients and their families navigate the uncomfortable waters of talking about end-of-life care and developing their POLST document.

POLST is an excellent tool for patients and families. It engages the individual in the decision-making process and, when used with an advance directive that names a proxy health-care decision maker, it helps ensure that care is provided based on the wishes of the person, including limiting care like intensive care unit stays or intubation. This protects against pointless suffering, and allows patients to know their wishes will be honored, even if they can’t personally enforce them. It also helps both patients and their families navigate the uncomfortable waters of talking about end-of-life care and developing their POLST document.

In my state, California, the California Health Care Foundation (CHCF) first provided $120,000 in grants to several communities to establish POLST programs. Based on their initial success, CHCF has made a series of investments through 2013 of over $3 million to spread POLST throughout California. The Coalition for Compassionate Care of California administers the funds. Since January 2009, California law has required that POLST be honored across all settings of care and gives legal immunity to providers who honor a POLST document in good faith.

Initially, our outreach and funding efforts have focused on patients in nursing homes. Too often, nursing home patients are shuttled back and forth to the hospital with every downturn in their health; once hospitalized, they may receive a full range of uncomfortable, even painful, tests and procedures. Very few nursing home patients want this, but their wishes are not know and honored. With POLST, patients and families can elect to curtail hospital trips, as well as instruct the hospital to use only limited interventions.

Impending death is an unpleasant subject, but it’s a part of life we can’t afford to ignore or deny, especially if we wish to give the people we love the gifts of respect and dignity that every human being deserves. So far, 11 states have fully adopted POLST, with an additional 20 states developing programs. But that still leaves 19 to go.

Kate O’Malley, RN, MS, is a senior program officer at the California Health Care Foundation.