Chris Langston, right, with his younger sister Anne, mother Adair, and grandmother Nancy Imber, circa late 1970s. Did someone with geriatric expertise make a difference in your family's life?

Chris Langston, right, with his younger sister Anne, mother Adair, and grandmother Nancy Imber, circa late 1970s. Did someone with geriatric expertise make a difference in your family's life?There are just four more weeks left in the John A. Hartford Foundation’s new Heroes of Geriatric Care story contest (due April 15—like taxes). We’ve received a few submissions (and a lot of questions), but we want more.

Part of the reason for having the contest is that we want to discover the variety of ideas and experiences out in the world without unduly influencing anyone’s thinking. Nevertheless at this point, I thought it might be helpful to give a few examples of geriatrics hero stories.

The challenge is to relate a story that captures the special value of expertise in geriatric care to the wellbeing of older adults and their families. My colleagues and I have already told many, many stories of the pain and suffering caused by the lack of expertise. Now we want to look on the bright side.

We want hero stories. And we’re offering a top prize of $3,000, along with the opportunity to have your story shared widely to support our mission to improve health care for older adults.

I will offer two examples: one personal from my family’s lore and one that I heard from one of our grantees.

So for a very simple personal story: In the last years of my grandmother’s life, she became frail and burdened with a wide variety of ills. She lived with my parents in California for several years before moving to a nearby assisted living facility, where she could receive a slightly higher level of care. Among the most obvious of her issues was the weakening of her skin, which became something like wet tissue paper—thin , easily torn, and not much protection. With the loss of the resilience and stretchiness of the skin and the padding of the muscle and fat under it, she bruised terribly at the slightest bump, her skin tore easily, and she suffered nosebleeds that were very hard to stop.

I remember one time when she had to be taken to the Kaiser clinic because she had somehow barked her shins while having her hair done at the beauty shop. Some of the doctors and nurses suspected elder abuse, not believing that so much damage could done by a bump. Fortunately, someone with more expertise in aging looked and assured them that it was consistent with her condition—to the great relief of my mother.

Other times she had to be taken to the clinic for nosebleeds that wouldn’t stop and eventually were cauterized—which sure sounds painful. But I remember my mother telling me with delight that at another nosebleed visit, a physician had avoided the cautery and inserted a Vaseline-coated cotton ball into the nose to keep the membrane moist and under pressure until the bleeding stopped. A simple thing, but an expertise that clearly not everyone had and something that made a difference in my grandmother’s life—perhaps a metaphor for the high touch, low tech value of geriatrics?

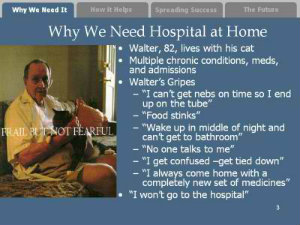

The other story I wanted to tell is that of Walter, which I first heard from Bruce Leff, MD, at Johns Hopkins. Walter was one of the patients in the Johns Hopkins-Bayview geriatrics division visiting-physician, home-based primary care practice. Like a lot of their patients, he was in his 80s and lived alone in East Baltimore with multiple serious chronic illnesses, including very serious COPD, which would require a trip to the hospital every few months.

The other story I wanted to tell is that of Walter, which I first heard from Bruce Leff, MD, at Johns Hopkins. Walter was one of the patients in the Johns Hopkins-Bayview geriatrics division visiting-physician, home-based primary care practice. Like a lot of their patients, he was in his 80s and lived alone in East Baltimore with multiple serious chronic illnesses, including very serious COPD, which would require a trip to the hospital every few months.

As Bruce tells the story, Walter hated going to the hospital—he didn’t like the food, they were late getting him his routine nebulizer treatments so he felt sicker, and there was no one to take care of his cat. Eventually, Walter said that he just wasn’t going to go back. The Hopkins team told him that he might die if he didn’t get hospital treatment for the flare-up of his condition, but he refused to go.

So the Bayview team began to bring hospital treatment to Walter. In what eventually became known as the Hospital at Home program {http://www.hospitalathome.org/}, equipment and staff came to Walter to provide hospital-level care for him at home. Clearly, this is a much higher tech kind of expertise than the care of my grandmother. But it also illustrates the “high touch” focus on the needs of the person rather than on the needs of the health care system. Walter recovered from the flare up and was able to stay home with his cat and have more time to do the things he wanted for himself.

And, as what began as a response to this case and others seemed to have wider applicability, the Hartford Foundation was able to support Bruce and John Burton, MD, and their many colleagues to develop the Hospital at Home model, refine it, and test it in a multi-site trial that showed that it had better clinical outcomes, lower costs, and higher satisfaction. To my mind, the story of Walter is a great example of how geriatrics expertise can be applied to meet the needs of older adults and society at large and how passionate and creative people can lead change.

I offer these only as examples of the kinds of stories we’re interested in getting, in the hope that they may inspire you to share your own. Don’t be shy, don’t be modest. How has expertise in geriatric care in the health care workforce benefited you or your loved ones? If you are a professional, how has your expertise enabled you to improve people’s lives more than colleagues who lack geriatric training?

So give yourself something to look forward to this Tax Day. Share a story that can help us better make the case for improved health care for older adults and draw others to join us in this important work.