I was recently at a site visit for federal policymakers to Baltimore to learn about the Foundation-sponsored Guided Care project directed by Chad Boult. I’ve already blogged about the trip, highlighting stories of some of the Guided Care patients we met. This time, I want to add some observations inspired by the comments of the physicians working with the Guided Care nurses.

In speaking about their experiences with Guided Care, the three physicians we interviewed were in a quandary. Although they said they enjoyed having a Guided Care nurse and admitted their work now went more smoothly, they could not quite bring themselves to say that patient care was better than before. One doctor started out with a story of how the nurse working with him had brought him the news of a contraindicated prescription in one of his patients. At first he said that it couldn’t be true because he knew he didn’t do things like that. But when confronted with the evidence, he had to admit that he had made a mistake.

In speaking about their experiences with Guided Care, the three physicians we interviewed were in a quandary. Although they said they enjoyed having a Guided Care nurse and admitted their work now went more smoothly, they could not quite bring themselves to say that patient care was better than before. One doctor started out with a story of how the nurse working with him had brought him the news of a contraindicated prescription in one of his patients. At first he said that it couldn’t be true because he knew he didn’t do things like that. But when confronted with the evidence, he had to admit that he had made a mistake.

Unfortunately, the physicians weren’t willing to make the same admission about Guided Care. They saw the evidence but balked at drawing the logical conclusion: their care was not as high quality before they received a Guided Care nurse. Several of the physicians said that without the nurse they would have done everything the same, but would just have taken longer.

While I have great sympathy for these beleaguered primary care physicians (and gratitude for their participation in the event and demonstration), this is frankly a ludicrous claim. Taking a few days or week to see a patient to correct a medication error or even answer a burning question can easily lead to a trip to the ER and then a hospital admission, with progressive reduction in health, vitality, and function for the older person. Care delayed is care denied.

In discussing the Guided Care model, one of the most thoughtful physicians acknowledged that his training as an internist had taught him not to trust anyone--if you don’t do it yourself, it probably won’t get done, or get done right. He also acknowledged that this mistrust really centers on non-physicians: doctors do learn to work on rounds with other physicians: fellows, interns, chiefs. He also commented that taking a more business-like approach to primary care with increased delegation of tasks to other members of the team (and requiring accountability for their performance) would probably be a good and efficient thing. The physician at my table, however, emphasized her strong sense of responsibility for all decisions made about patient care.

While it sounds good and virtuous, this claim of “responsibility” is itself irresponsible. I know it is reinforced by strong tradition as well as fear of legal responsibility. Yet not only does it create a situation where quality care simply cannot be delivered because a single individual makes him or herself a bottleneck for all actions and decisions, but it has made primary care medicine an entirely unattractive field of medicine that students are avoiding in droves. I remember another presenter at a National Health Policy Forum meeting several years ago describing the results of her time in motion calculations based on typical patient panel size and the number of guidelines and prevention requirements that need to be covered in primary care. It turns out there just aren’t enough hours in the day for an individual physician to do it all. Working harder cannot solve the problem. Working smarter with help from other health professionals is the only direction possible.

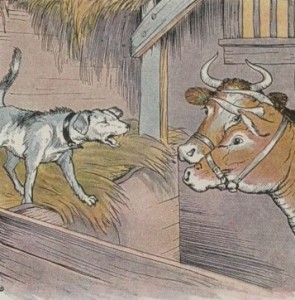

Too often, physicians are patient care “dogs in the manger”--unable or unwilling to do the work, but unwilling or unable to let anyone else do it either. The end result is it just doesn’t get done. How can we do things differently? How can we encourage physicians to delegate and share the workload--while assuaging fears of loss of control? We certainly can’t keep the status quo--for physicians to stand pat on their laudable sense of responsibility to their patients is, in itself, irresponsible.