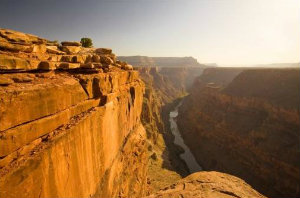

There is a yawning chasm between the health care system we want and what we have. Crossing that gorge will be a messy and inconvenient process—but necessary.

There is a yawning chasm between the health care system we want and what we have. Crossing that gorge will be a messy and inconvenient process—but necessary.While many of us in the geriatrics community were wending our ways home from the 2013 American Geriatrics Society conference in Dallas with dreams of improved care for older adults dancing in our heads, respected health services researchers Stephen Soumerai and Ross Koppel published a Wall Street Journal opinion piece with a stinging attack on Medicare’s new hospital readmissions penalty program.

We’ve talked about the need for healthy policy debates on readmissions policies before, and as a funder of the work of Eric Coleman, Mary Naylor, and the Society of Hospital Medicine’s Project BOOST to reduce hospital readmissions for older adults, I’d like to continue the discourse by responding to the major points made by Drs. Soumerai and Koppel.

Because the WSJ keeps material behind a pay wall, I will briefly summarize their arguments against the readmissions penalty policy and then offer my comments.

First, they argue that research shows that most readmissions can’t be prevented and cite research at the University of Toronto published in 2011. I believe that the source is this meta analysis of other’s research on “preventability ratings” of readmissions which concludes that the aggregate result is 27.1 (range 5-97 percent) or “only about 25 percent of readmissions are preventable.”

Drs. Soumerai and Koppel argue that “readmissions are often unavoidable consequences of life-threatening complications that can appear after discharge.” As readers of our blog know, yes, life-threatening complications can arise after discharge, but not at random and not that can’t be predicted or reduced. For example, Rachael Watman’s father had a readmission for “life-threatening complications” after bypass surgery, but the cause was that a key medication had been left off the discharge plan—not something that couldn’t be foreseen or prevented by a better system. In fact, according to Eric Coleman’s research, very high rates of medication errors and lack of reconciliation are the very preventable cause of many readmissions.

Moreover, rhetorically, even the word “complication” in the sentence quoted above subtly suggests that the exacerbations and panics that drive hospital readmissions are somehow inevitable, uncontrollable, and out of our hands. The more straightforward term is adverse event—sometimes preventable and sometimes not.

If, as Jenks, Coleman, and Williams showed in 2008, the readmission rate for medical condition hospitalizations was 19.6, a 25 percent reduction in this rate would be almost 5 percentage points and represent a very substantial reduction in overall health care utilization and cost—probably taking a hospital out of the “penalty” zone. By the way, the penalty program does not require that a hospital have a 0% rate of readmissions, only that its rate is not high compared to other hospitals. Plus, the program already has some risk adjustment built in.

Second, Drs. Soumerai and Koppel argue that readmissions penalties will have harmful consequences, particularly to the most vulnerable, because hospitals will try to game the system by avoiding admitting patients in the first place if they look like they might be readmission candidates. This is predicted to lead to more use of ER “observation” stays and other poor care.

This is clearly an important issue—but it is also an argument that hospitals (and their staffs) do respond to payment incentives. They may not always respond as one predicts, but they do respond—contrary to what Drs. Soumerai and Koppel contend. And more importantly in my view, this is an example of the need to distinguish fraud from system error. There is a point where responding to financial incentives becomes intentional fraud and should be subject to penalties under the law. Hospitals that fail to provide necessary services out of economic motives (e.g., “ER dumping”) are engaging in criminal acts and should be treated as such, not coddled.

Health care is a business like others—there will always be an opportunity to make a buck by cutting corners (e.g., selling contaminated drugs) and when bad behavior moves from error or system dysfunction to willfully planned efforts to profit illegitimately, people and organizations should be held accountable.

Third, the authors argue that the policy “discriminates against poorer hospitals.” (And since poorer hospitals typically serve poorer people, also against poor people.) They cite a Commonwealth study that showed that “safety net” hospitals have higher rates of readmissions on average. They argue that thin-margin hospitals will not be able to improve their readmissions and suffer these penalties, by implication reducing access for poor people.

I have heard this critique from stakeholders ranging from the business side of health care to the patient’s rights advocates and it makes me very frustrated. It seems to be an argument that boils down to this: Poor people should be satisfied with mediocre care that doesn’t meet their needs because they are poor and high rates of readmission and other defects must be tolerated as an unchanging and unchangeable status quo.

I think that if a health system sees again and again that patients return to the hospital because they have trouble getting medicines, trouble getting follow-up appointments, and trouble understanding self-care instructions, there are cheap and relatively easy steps that will work and should be tried. If you are in a hole and want to get out, the first step is to stop digging. Stop doing the things that you already know won’t work—like skimping on discharge instructions, translation services, failing to have discharge plans (and planners) connect to social services—and try something different and keep trying until something works.

In the BOOST program, for example, hospitals make sure that patients have their medicines when they leave the hospital, help patients make follow-up appointments, and make calls to check on early post-discharge progress. This isn’t expensive and, in fact, I think most people would think these are reasonable things to do under all circumstances. After all, when I check a car out of the rental company, it is full of gas and they have maps to offer me. I don’t have to immediately fill up or call back for directions.

(Hospitals can visit the Society for Hospital Medicine website to learn how to implement BOOST.)

Drs. Soumerai and Koppel recommend funding models that use “physician-nurse practitioner teams” as shown by real randomized clinical trial data “from Yale and other prestigious institutions” to reduce readmissions.

This sounds like Mary Naylor’s work from Penn (which, by the way, they say sometimes can reduce readmissions by 50 percent! So maybe that 25 percent number is too pessimistic?)

The authors argue that penalties for problems like hospital-acquired infections haven’t worked and just lead to gaming. And they argue against pay-for-performance schemes overall. They advocate for more “training and mentorship—not blame and punishment.” This is a usual and reasonable view held by the quality improvement movement overall, which argues that failures are system products, not the work of ill will or defects of an individual person.

I would interpret these arguments as being for a “carrot” rather than “stick” approach to driving change. We certainly believe that good models of care should be supported and made available (carrot). But the implication of the opinion piece that training and support are not available for models that work is misleading.

We at the John A. Hartford Foundation are funding Dr. Coleman to provide training in his Care Transitions Program, while the federal Partnership for Patients, through the Medicare and Medicaid Innovation Center, is spending $500 million on training and mentorship of hospitals, largely through American Hospital Association affiliate chapters that help hospitals address a list of 10 quality problems of which readmissions is the 10th.

And the other $500 million of the Partnership for Patients (the Section 3026 Community Based Care Transitions Program) provides funding to community-based care teams to partner with hospitals to reduce readmissions. All of the new funding models currently being tested, such as Accountable Care Organizations and bundled episode payments, give a positive incentive to hospitals to reduce costs and improve quality. These models allow them to share in whatever savings are achieved.

The unfortunate truth is that I have heard with my own ears from hospital administrators that “yes,” they do know they could and should reduce readmissions, but until the perverse incentive to make more money on more readmissions is gone, they won’t stop. I’ve heard even more of our geriatrician friends describe how programs and models of care that improve the health of older adults and reduce admissions and readmissions, are, in fact, discontinued because they were effective.

There are already incentives in health care and they don’t serve patients’ or society’s best interests right now. Getting the new incentives right will be difficult and require course corrections and vigorous argument and debate.

But we have to stop digging ourselves into a hole if we ever expect to get out.