The last several weeks have been extraordinarily busy ones for policy proposals relevant to health care for older Americans. First, on March 31st, the long awaited proposed rule for the "Medicare shared savings program" authorized under section 3022 of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act was announced by Dr. Don Berwick, head of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). Then on April 12th the application process and rules for the Community Based Care Transitions Program authorized under section 3026 was announced as part of a sweeping Partnership for Patients initiative. And, of course, proposing to change the game completely, Representative Paul Ryan, Chair of the House Budget Committee, released his plan to shift Medicare to a defined contribution program using a premium support mechanism as part of the Committee's "Path to Prosperity" budget proposal.

The last several weeks have been extraordinarily busy ones for policy proposals relevant to health care for older Americans. First, on March 31st, the long awaited proposed rule for the "Medicare shared savings program" authorized under section 3022 of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act was announced by Dr. Don Berwick, head of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). Then on April 12th the application process and rules for the Community Based Care Transitions Program authorized under section 3026 was announced as part of a sweeping Partnership for Patients initiative. And, of course, proposing to change the game completely, Representative Paul Ryan, Chair of the House Budget Committee, released his plan to shift Medicare to a defined contribution program using a premium support mechanism as part of the Committee's "Path to Prosperity" budget proposal.

Despite the controversy around the proposed solutions, the "good news" is that it is clear to everyone that improving health care for older Americans is vital not only for their health and well-being but also for the economic future of the country. Unfortunately, the bad news is that the key value proposition that the Foundation has been trying to advance — that there is special expertise needed for geriatric care and that putting it to work effectively requires deploying a better trained workforce in new and different ways— does not seem to be at the top of any one's mind. With the possible exception of the Community Based Care Transitions Program, which is closely based on the work of Foundation grantees Eric Coleman and Mary Naylor, these proposals give far too little attention to workforce: Who is supposed to do the new work? How have they been trained? and How will we help them redesign their work?

Despite the controversy around the proposed solutions, the "good news" is that it is clear to everyone that improving health care for older Americans is vital not only for their health and well-being but also for the economic future of the country. Unfortunately, the bad news is that the key value proposition that the Foundation has been trying to advance — that there is special expertise needed for geriatric care and that putting it to work effectively requires deploying a better trained workforce in new and different ways— does not seem to be at the top of any one's mind. With the possible exception of the Community Based Care Transitions Program, which is closely based on the work of Foundation grantees Eric Coleman and Mary Naylor, these proposals give far too little attention to workforce: Who is supposed to do the new work? How have they been trained? and How will we help them redesign their work?

It should be clear to everyone that improving care and lowering costs are challenging tasks individually and incredibly tough taken together. We need to understand thoroughly all the available evidence of what works and what does not before jumping into these programs. In the next few weeks I will try to offer some analysis of each of these proposals starting with the proposed rules for Accountable Care Organizations. The Internet is rife with general analysis of the proposed ACO program and some of its surprising features – for example here and here – and a brief thumbnail of the program is included at the end of the post.

For today's comments, I searched a variety of key terms to see how the rule addresses some of the special needs of older adult patients. I searched the proposed rule for "geri*" and found a discussion of how ACOs will define their patient population - i.e., people who get the majority of their primary care from the ACO's primary care providers (physicians in internal medicine, general practice, family practice, or geriatric medicine - but oddly not nurse practitioners or physician assistants who are PCPs). To the extent that ACOs in development need to identify 5,000 Medicare beneficiaries who get their primary care services from affiliated PCPs, this principle could be good for geriatricians. Instead of being looked down upon as the kind of provider who attracts complexly ill patients with little profit margin, now geriatricians will be the docs who can bring large numbers of ACO participants to the table.

Even better, having geriatricians and their complex patients will also help defend an ACO from accusations of cherry picking and avoiding "high risk" patients who are likely to be high users of services. One of the clear threats to the sustainability of the ACO model is if ACO's are able to keep out high-need patients and by virtue of selection trickery alone, make it look as if they have "saved" money. CMS clearly intends to monitor its ACOs closely for patient selection practices that smack of cherry picking. Alternatively, CMS could just be extra careful in how it builds its comparison spending models - if an ACO spends little on patients for whom little spending would be predicted, that is not savings.

This brings me to my biggest gripe. What about the highest need geriatric populations - e.g., those who are very frail, cognitively impaired, have multiple chronic diseases, or live in nursing homes? If ACOs are to succeed on their own financial terms and in terms of bending the nation's cost curve, these are the patients whose care they most need to improve and where there are the biggest savings to be had. You can coordinate the heck out of the care of a well 65-year-old, but no intervention can save money where it wasn't going to have been spent. Only sick people have hospitalizations that are both frequent enough and predictable enough to be targeted for interventions. As palliative care has shown us, even very, very sick people have room for both improved care and reduced service use/costs.

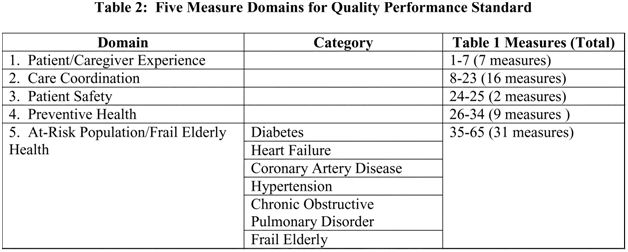

While there is nothing that precludes these patients from being "in" an ACO, there is nothing that facilitates it either. Moreover, there is relatively little in the proposed patient care quality measures that focus on the special needs of this population. While the chart below shows 31 measures for "At Risk Populations/The Frail Elderly," only the last three are categorized as specific to the frail elderly: 1) annual screening for falls, 2) measures of osteoporosis care in women with fractures, and 3) monthly measurement of appropriate dose for those on Warfarin (blood thinner). With the exception, (again) of Coleman's Care Transitions Measure and related items, the care coordination measures have little to do with care coordination but largely reflect treatment of ambulatory sensitive conditions that may reduce hospitalization. In fact, the criteria for Medicare's new Annual Wellness Visit seem substantially better as measures of quality than these.

Fortunately, one of the purposes of the proposed ACO rule is to solicit feedback. We all have until June 6 to submit comments. Citing file number CMS–1345–P comments may be submitted through www.regulations.gov. I hope that the community of people who want to improve care of older adults will vigorously participate and help make this program a success.

************************************************************************************************

For those of you who haven't been following the ACO idea until now, the proposal is intended to thread the needle between the perceived sins of 1990s-era managed care (restriction of choice and under-treatment) and the excesses of present-day fee-for-service (fragmentation, high costs, and over-treatment). It also is designed to be a way that the current fee-for-service oriented physicians and hospitals can get started becoming more like the icons of integration such as Kaiser and Geisinger without radical changes in ownership and governance.

Mechanically, as set out in section 3022 and in the proposed rule, an ACO is a formal contractual organization of physicians and hospital(s) that will be held accountable for the costs and quality of care for a specified population of beneficiaries/patients. This beneficiary population is defined by their engagement with primary care physicians attached to the ACO. Financially, in addition to providers' usual revenue from fee-for-service billings to Medicare, they stand to share in any savings to Medicare outlays (as compared to what would have happened) for these patient/beneficiaries, assuming that cost reduction meets agreed upon targets while also meeting quality targets.

The program was piloted in the Medicare Physician Group Practice Demonstration featuring Foundation-related institutions such as the University of Michigan, led by Caroline Blaum, and Dartmouth, led by Elliott Fisher and geriatrician/Beeson Scholar Julie Bynum.