In what ages of life does one most need the advice of a doctor who understands rapid changes in the body and mind and can help keep you on a healthy course for the future?

In what ages of life does one most need the advice of a doctor who understands rapid changes in the body and mind and can help keep you on a healthy course for the future?

Most people know that this is one of the key functions of a pediatrician. Indeed, two of my three children have had small developmental abnormalities (one speech and one vision) detected and successfully put back on course before they had any big disabling consequences. What fewer appreciate is that people moving from middle age (whatever that is) and on through older adulthood have the same need for an expert in their stage of development, a geriatrician.

After a good long period of almost undetectably slow physical decline from the 20s to the 50 or 60s, at some point in the aging process there is again a period in life when one can get off course. There are many ways in this stage of life to go off course, often involving well meaning but mistaken health care. Under treatment, over treatment, or just plain mistaken treatment can all be dangerous. However, with expert advice, including medical advice, aging can be better than we may fear (although not optional, as many seem to believe).

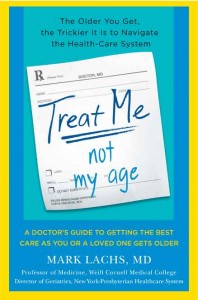

Mark Lachs, M.D. M.P.H., a geriatrician, is Professor of Medicine and Co-Chief of the Division of Geriatrics and Gerontology at Cornell University’s Weill Medical College. He is also director of Cornell's Center for Aging Research and Clinical Care and Director of Geriatrics for the New York-Presbyterian Health System. Treat Me, Not My Age: A Doctor's Guide to Getting the Best Care as You or a Loved One Gets Older is his engaging reflection on how the inexorable biological processes of aging interact with our physical and social environments, giving rise to health or catastrophe. It is salted with humor and wistful anecdotes, including a reflection on the life of Mickey Mantle. Mantle gave us the essence of regret over lost health opportunities when he said, "If I'd known I would live so long, I would have taken better care of myself."

![]()

Dr. Mark Lachs speaks with Good Morning America about Treat Me, Not My Age.

Dr. Lachs is an old friend of the John A. Hartford Foundation; he was in the first cohort of Paul B. Beeson Career Development Awards in Aging Research in 1995. Although his primary area of research is in elder abuse and the disadvantaged elderly, this book is for everyone: older adults from all economic backgrounds and their families. The book covers a tremendous range of issues: primary care, mental health, hospitals, post-hospital rehabilitation, long-term care, financial planning, life planning, home modification, and so on. This breadth is required because of the way that everything in an aging person’s life is interconnected. For example, a person who cannot walk up five flights of stairs is disabled if he lives on the top floor of a New York City walk-up. In most of the rest of the country, a person who loses the ability to drive is also disabled. This disability will then have social, financial, physical, and even spiritual consequences when one is forced to move.

Some will no doubt be disappointed that the book does not offer quick-fix (quack-fix?) advice about weird food supplements or fad diets, or even this minute's scientifically recommended doses of vitamin D. Rather, it is more firmly based on knowledge of aging and the many things that can be done to reduce its impact on the important things in life. Two core concepts organizing the book are 1) "excess disability" is far too common and 2) there are things that health professionals and people can do to prevent this avoidable loss.

As Lachs puts it, the embers of disability begin to smolder early, often nurtured by poor lifestyle choices that we make. These glowing coals then are ready to burst into flames when an accident, routine illness, or well-intended health care treatment comes our way that overtaxes our declining reserves. When this kind of flare-up occurs, it can lead to heartbreakingly rapid decline and needless suffering. But it need not be so.

One of my core frustrations of working in aging and health care is that people rarely want to hear about the physical decline and health care realities of aging before it is too late. I think that in this book Dr. Lachs has succeeded in making the information interesting, funny, and thought provoking enough that his book will be helpful to people in their 40s and 50s. Of course, it will be very useful to today's older adults and those caring for family members in need, even if it will no doubt make some people say, "If only I had known . . ."