Reflecting on The Gerontological Society of America’s (GSA) annual meeting, I am more confident than ever that teamwork and interprofessional collaboration are essential to improved care of older Americans. From the fabulous research work, to the clinical teams, to the interprofessional education efforts, I saw examples that made me sure that this is at the core of good care for older people and therefore an important direction for the Hartford Foundation.

Reflecting on The Gerontological Society of America’s (GSA) annual meeting, I am more confident than ever that teamwork and interprofessional collaboration are essential to improved care of older Americans. From the fabulous research work, to the clinical teams, to the interprofessional education efforts, I saw examples that made me sure that this is at the core of good care for older people and therefore an important direction for the Hartford Foundation.

I suppose that interprofessional collaboration was at the top of my mind because on my way from New York to the GSA meeting in San Diego, I had stopped for a site visit at the University of Minnesota to learn about the Health Resources and Services Administration’s (HRSA) newly funded $4 million National Center for Interprofessional Education and Colaborative Practice.

My colleagues and I visited the center as part of a consortium of funders interested in the issue who have been working with HRSA in designing and reviewing proposals for the center and who hope to add more even more support, building upon HRSA’s investment to advance this national agenda. I wouldn’t normally write about a grant in development for HealthAGEnda, at the very least for fear of bad luck, but in this case I think that our readers and stakeholders deserve to know what we are thinking and what is going on.

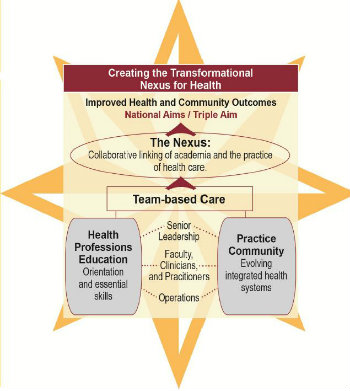

Directed by Barbara Brandt, PhD, Vice President for Education at the University of Minnesota, the new center, now called the National Center for Interprofessional Practice and Education, is intended to be the hub of a national movement to advance the Triple Aim agenda in health care—improved quality of care, better health for the population, and lower per capita expenditures. A primary focus of the center is the “nexus” of aligning health professions education and the transforming health care system. (For more information, see Brandt’s overview presentation to the IOM’s Global Forum on Innovation in Health Professional Education.)

Directed by Barbara Brandt, PhD, Vice President for Education at the University of Minnesota, the new center, now called the National Center for Interprofessional Practice and Education, is intended to be the hub of a national movement to advance the Triple Aim agenda in health care—improved quality of care, better health for the population, and lower per capita expenditures. A primary focus of the center is the “nexus” of aligning health professions education and the transforming health care system. (For more information, see Brandt’s overview presentation to the IOM’s Global Forum on Innovation in Health Professional Education.)

As many readers might be aware, the Foundation has long seen interdisciplinary training for health professionals as key to high-performing team practice. And, of course, high-quality team practice is key to providing efficient and effective care to older Americans. Given the breadth and complexity of biological, psychological, and social needs that older people can face, only teams representing a wide range of skills deployed in exquisite coordination can meet those needs.

The Foundation’s last major effort, Geriatric Interdisciplinary Team Training (GITT), began with planning grants in 1995 to many institutions followed by operating site grants to nine institutions, a national resource center for technical assistance at NYU’s Hartford Geriatric Nursing Institute, and an overall evaluation center at UCLA’s multi-campus program in geriatrics and gerontology. In all, we spent well over $10 million of our money and at least that much in matching funds. (For more information, see our 2000 annual report.)

Despite this major investment, I feel we achieved relatively little lasting impact—and certainly not at a national level. In part, we were just ahead of our time. Also, our approach was almost entirely supply side—developing curricula and faculty at specific institutions—without enough attention to the broader forces that shape health professions training, such as payment and professional regulations. We did follow GITT with Geriatric Interdisciplinary Teams in Practice (GIT in P) and also our interdisciplinary research center program with RAND. Both of these initiatives had perhaps more modest aims and clearer results. We are very proud of both the specific patient outcome and research program outcomes of these initiatives, as well as the evidence they add to the growing pile on the value of teams in care and research.

Still as we face the brave new world of health reform and delivery system improvement, it is nerve racking how dependent our hopes are upon high-performing teams, both colocated and virtual. For example, for medical homes to deliver more effective primary and preventative care, the bottleneck of the MD:Patient face-to-face visit needs to be eliminated. Not just the face-to-face part, but also the excessive focus on the work of the MD. Whatever can be done by other professionals should be. Moreover, many things that are not even part of the physician skill set and not part of typical current practice must be done to improve outcomes, such as addressing social circumstances and family caregiver issues.

Similarly in accountable care organizations (ACO), bundled episode payment models, and integrated plans for Medicare-Medicare dually eligibles, providers who didn’t even think of themselves as being on the same team must adopt a vision of shared responsibility for patient outcomes and give up preconceptions and adversarial habits (nursing home versus primary care physician, versus hospital, versus social service agency) and learn to succeed together.

But where is this mentally redesigned workforce to come from? Having been burned our GITT efforts before, we were enthused but content to root from the sidelines when a few years ago the Josiah Macy Jr. Foundation—under the leadership of its then new President, George Thibaux, MD—began to take up the charge.

But as the scope of Macy's work continued to grow to a nationwide series of grants and found allies and support in the Interprofessional Education Collaborative, it became an opportunnity we could not refuse. This time, instead of funding many individual schools (which Macy Foundation is currently doing), our focus will be on a national center intended to partner with institutions and stakeholders all across the country and build the field in a way that will make Interprofessional Education and Collaborative Practice the new norm in health care.

Despite our view that interprofessional education and collaborative practice represent a rising tide that will “lift all boats” and improve the care of older adults, we also wanted to add two specific charges to the work of the national center in exchange for our support.

First, we think that perhaps 20 percent of the focus of the national center should be on the care of older adults. Older Americans with complex needs are ideal cases for interprofessional education and already use an even larger share of health care resources (for example, almost half of hospital bed/days). But we know that it will be hard to make a focus on their care meaningful with the shortage of geriatrically expert faculty and truly appropriate practicum/clinical training sites.

Second, while social work was left out of this current interprofessional education movement for largely accidental historical reasons, we feel that it is a key discipline which most directly addresses the social needs that are at the root of much that health care tries to treat. For that reason, we also have requested that social work and social workers be included in the work of the center. We are not quite sure how to operationalize these requirements, much less how the center will implement them, so we would be grateful for any suggestions from our readers.