This month in the Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, there is a short editorial reporting on a national movement that has been more than 12 years in the making. In the paper, titled Self-Management at the Tipping Point: Reaching 100,000

This month in the Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, there is a short editorial reporting on a national movement that has been more than 12 years in the making. In the paper, titled Self-Management at the Tipping Point: Reaching 100,000

Americans with Evidence-Based Programs, long-time National Institute on Aging leader Marcia Ory, PhD, along with luminaries such as Kate Lorig, DrPH, of Stanford, and Nancy Whitelaw, PhD, Senior Fellow at the National Council On Aging (NCOA) and past president of the Gerontological Society of America, discuss the long journey to reach the 100,000th older adult with evidence-based health promotion services.

While the most important part of this story has been the thousands of community-based agencies around the country that have adopted and offered evidence-based programs that improve the health of older Americans, there have been terrific partnerships behind the scenes among many funders, researchers, and leaders of the movement.

And I’m pleased to say that today, the John A. Hartford Foundation trustees approved a grant to help the evidence-based movement take its next steps. More on that in a minute.

For the Hartford Foundation, our participation started in 2001 as our hopes for our Generalist Physician Initiative and of comprehensive primary care more generally were quietly collapsing. We had gone into that program and much of our Integrating and Improving Services work with the notion that primary care practices needed to offer a much broader set of services to meet the needs of aging people.

And we had paid for a wide variety of new models using extra staff to test the concepts. In 1999 and 2000, we had also massively expanded our academic capacity work in social work and nursing, preparing faculty and curriculum to help train social workers and nurses to be more effective parts of the geriatric care "team" of the future.

Unfortunately, the cultural and even physical limitations of the primary care environment had made it clear that medical practices were simply not the right home for many of the social and health promotion services that we remained convinced could help older people retain their health and independence.

Moreover, as Medicare managed care hit a national low and the grand vision of integrated health care organizations splintered, it also became clear that there was not going to be any financing mechanism whereby health care spending might be shifted to preventive services—even if we could produce evidence that it lowered total costs.

As we licked our wounds and considered our options, we recognized that there was already a significant national infrastructure delivering "social" services to older adults through the aging services network coordinated by the then-Administration on Aging. While the $2 billion Older Americans Act appropriation was pretty small-time even compared to the Medicare and Medicaid spending of the time, it was still a flow of funds that supported a wide variety of programming around the country.

We therefore changed our goal from a strong form of integration to a looser form of partnership between the medical world (the part supported by Medicare) and the social service world based in community agencies and paid for by the Older Americans Act.

In 2001, The National Council on Aging, with funding from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, had just completed a large-scale survey of the nature and extent of services provided by community-based agencies to older adults and work was already under way to explore how such agencies could partner with "medical" care organizations to improve the outcomes of their common beneficiaries.

Based on our experience at the Hartford Foundation, we thought that such partnerships were important to foster. But we also believed that increasing the quality of the programming offered by community agencies was a key prerequisite. I wrote in our 2001 "Summary and Analysis" document prepared for the board of trustees as they considered a $1.3 million grant to NCOA for evidence-based programs:

Unfortunately, the potential impact of these services on older adults’ health is limited by two problems. First, the quality and consistency of programs offered by community-based agencies to address issues such as exercise, nutrition, and socialization is highly variable. While medicine has gradually awakened to the issue of undesirable variability in its practices and procedures and the need to make decisions based on outcomes for patients, community-based programs are not as advanced in creating evidence-based national standards and guidelines for effective programs. Second and relatedly, the full benefits offered by community-based programs will not be realized until they are recognized as an important part of the continuum of care and there is greater coordination between them, physicians, hospitals and other parts of the traditional medical system.

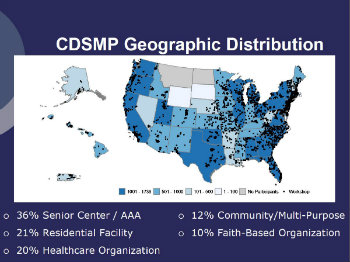

Despite some concerns, the grant was approved and gave birth to several specific evidence-based programs that have lasted: Healthy Ideas, Healthy Moves, and Healthy Eating. These programs were further nurtured in their development by the AoA and joined such powerful programs as A Matter of Balance, EnhanceFitness, and, of course, The Chronic Disease Self Management Program (CDSMP) as part of the nation’s armamentarium.

Despite some concerns, the grant was approved and gave birth to several specific evidence-based programs that have lasted: Healthy Ideas, Healthy Moves, and Healthy Eating. These programs were further nurtured in their development by the AoA and joined such powerful programs as A Matter of Balance, EnhanceFitness, and, of course, The Chronic Disease Self Management Program (CDSMP) as part of the nation’s armamentarium.

But more important than the specific models was the growing appreciation that social services were "serious" and deserved to be treated as such by government, the health care world, and by their providers. In my mind, the fundamental argument of the evidence-based movement to social service agencies is: "What you do is serious, and it merits all of the research and testing that we require for other powerful interventions."

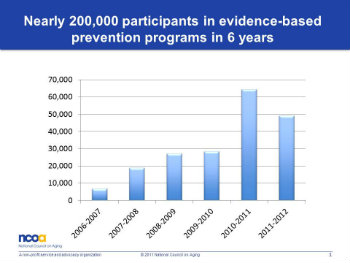

Now, more than 12 years later, the evidence-based movement has matured. Models have spread with continuous support of the AoA (now the Administration for Community Living) and a push of special support from the American Reinvestment and Recovery Act. The Chronic Disease Self-Management Program, in particular, has reached 100,000 people—far fewer than could benefit, but still representing a very significant infrastructure.

Nancy Whitelaw, PhD, Senior Fellow at NCOA

Nancy Whitelaw, PhD, Senior Fellow at NCOA(For more information, the NCOA has produced an excellent overview on evidence-based programs.)

In the new (again) environment of integrated health plans and many pay-for-performance mechanisms, we once again see the tremendous potential for partnerships between community agencies and health care to deliver high quality, comprehensive and coordinated care to older adults.

Which brings us to today’s decision by our board to approve a $2,068,500 grant that will support the Partners in Care Foundation in Los Angeles and Elder Services of the Merrimack Valley to form consortia of cooperating community-based agencies, increase access to and consistency of the evidence-based services they provide, and work with health care plans and providers as real partners. We think that the health promoting services delivered through community agencies are serious “treatments” and need to be a part of the plan for older adults.

We've been granted a second chance to advance comprehensive care and we must not squander it.