EDUCATION: Roberto

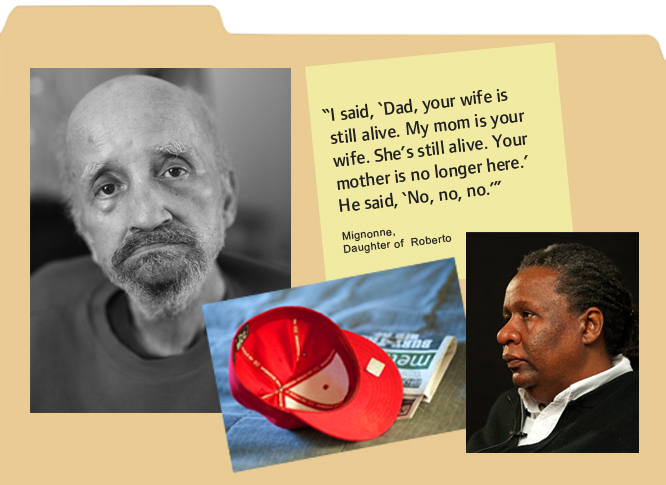

–Mignonne, daughter of Roberto

Roberto suffered from delirium after a fall.

Roberto suffered from delirium after a fall.

It became clear there was something more serious than depression going on. He clearly had delirium and we needed to address it. I was glad to have a student with me that day because this was a good teaching case. Ashley had the opportunity to evaluate the patient, review his chart, and communicate with his primary care providers to tease out what might be causing the delirium. She also followed him over time as he improved. It’s wonderful to see how well he’s doing now.

Pamela Z.Cacchione, PhD, RN, BC

Advanced Practice Nurse, Living Independently For Elders (LIFE)

Associate Director, Hartford Center of Geriatric Nursing Excellence

University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing, Philadelphia, PA

Roberto recovered from delirium because Pamela Z. Cacchione and her student, Ashley King, recognized the condition.

Roberto recovered from delirium because Pamela Z. Cacchione and her student, Ashley King, recognized the condition.

Treating Roberto was an excellent learning experience. We went to assess him for depression and we determined that he was actually delirious. He had an acute onset of change in mental status. It was fluctuating and he was disoriented. It was a marked change from his normal behavior. I was able to identify these features of delirium because of a required course I took at the University of Pennsylvania called Mental Health and Aging. Once the delirium was treated, Roberto left the nursing home and moved to an independent, supportive living environment.

This was an eye-opening experience and helped me to realize how nurses can treat acute and chronic mental health conditions and really improve quality of life. I can now definitely see myself focusing on an older adult population.

Ashley King, MSN, RN

Advanced Practice Nurse, Center for Family Guidance

Marlton, New Jersey

All Nurses Need Skills to Care for Older Adults with Mental Health Issues

Interdisciplinary team meetings, like those held at LIFE with the participation of nurses and nursing students, provide a holistic approach to physical and mental health care needs of older adults.

Interdisciplinary team meetings, like those held at LIFE with the participation of nurses and nursing students, provide a holistic approach to physical and mental health care needs of older adults.

Mignonne, daughter of Roberto

Roberto’s case was particularly complex, and having a nurse recognize his delirium and make sure he received effective treatment meant that he could eventually leave the nursing home and live in a supportive housing environment. After falling at home and not being found for 24 hours, Roberto was hospitalized. He had a breakdown of his muscles (rhabdomyolysis) and kidney failure. His daughter immediately noticed a change in his mental status, but she did not understand what it meant.

What is Delirium?

Delirium is a sudden, fluctuating and usually reversible state of mental confusion that affects up to 50 percent of hospitalized older adults. People with delirium may be disoriented and have memory problems. They have difficulty thinking clearly, focusing, and paying attention. They also may be agitated, have sleep disturbances, and in some cases have hallucinations (for example, hearing or seeing something that is not there) and delusions (false beliefs).1 Older adults with delirium are more likely to have longer hospital stays, more functional impairment, delayed rehabilitation, more frequent hospitalization, and higher mortality.2 Causes of delirium include an underlying medical condition (such as a urinary tract infection), medications, or withdrawal from medications.Delirium may be mistaken for dementia, depression, or psychosis because of similar signs and symptoms. Dementia is irreversible and results in a slow, progressive decline in memory and other cognitive functions. With delirium, a person can go from being cognitively intact to cognitively impaired very quickly, and it tends to fluctuate throughout the day. The diagnosis may be complicated because delirium can occur along with dementia. In fact, having dementia is a risk factor for delirium.

Recognizing delirium is important because it indicates that there is a medical condition that must be identified and treated. The underlying condition is not always readily identifiable, and there may be more than one cause. In up to one-half of older adults with delirium two or more conditions are responsible for the delirium. Delirium is treated by correcting the underlying problem and managing the behavioral and psychiatric symptoms.

Dr. Cacchione brought nursing student Ashley King, and the two of them determined that Roberto had signs of delirium, such as inattention, fluctuating levels of consciousness, and acute onset of delusions. They also discovered he had a hospital-acquired bowel infection. The infection was causing diarrhea and was the actual cause of the weight loss.

Working with a team of health care professionals, they determined that the delirium had multiple causes. It most likely began in the hospital with an electrolyte imbalance related to the rhabdomyolysis and kidney failure. The bowel infection that became apparent when he was in the nursing home caused dehydration and a further electrolyte imbalance. These exacerbated the delirium.

Roberto was treated with intravenous fluids, antibiotics, and other appropriate interventions focused on keeping him safe and functioning. This resulted in gradual improvement of both his physical and mental status.

“My dad got so much support from the nurses and social workers at LIFE,” says Roberto’s daughter, Mignonne. “If it hadn’t been for them I wouldn’t have known what to do with him. He probably would have ended up staying in the nursing home permanently.”

“When I told my dad he was moving to supportive housing and brought him his key he was ecstatic. He told everyone, ‘I’ve got my own place’.” Roberto continues to go to the LIFE day center three days a week where he can socialize with other members and receive primary and mental health care and rehabilitation services. He still has some memory problems, but he no longer has delirium.

“The fact that Roberto was able to leave the nursing home was a huge accomplishment,” says Dr. Cacchione. This probably would not have happened if it hadn’t been for a nurse with the knowledge and skills to identify the problem and make sure he received the appropriate care.

Improving Mental Health of Older Adults

Nursing student Ashley King learned important lessons as part of family meetings and the interdisciplinary team of health care providers focused on Roberto’s recovery.

Nursing student Ashley King learned important lessons as part of family meetings and the interdisciplinary team of health care providers focused on Roberto’s recovery.

the care of older adults suffering depression, dementia, and other mental health disorders.

The leaders of the GPNC hail from three of the Hartford Centers of Geriatric Nursing Excellence—Cornelia Beck, PhD, RN, Louise Hearn Chair in Dementia and Long-term Care and Professor, College of Medicine and College of Nursing, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences; Kathleen C. Buckwalter, PhD, RN, Professor Emerita, University of Iowa; and Lois K. Evans, PhD, RN, van Ameringen Professor in Nursing Excellence, University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing.

“Rather than develop a new subspecialty area—advanced practice nurse in geriatric mental health—we decided we could get a bigger bang by making sure all nurses have basic competence in recognizing and assessing mental health issues and providing basic care,” says Dr. Evans. Accomplishing this required building awareness in schools of nursing and compiling curriculum materials that faculty can easily access.

In this case, the GPNC articulated the essential knowledge and skills required to assure that high quality mental health care is provided to older adults.

With assistance from a home health aide Roberto is able to live independently. He travels several times a week by van to the LIFE day center to socialize and receive health care services.

With assistance from a home health aide Roberto is able to live independently. He travels several times a week by van to the LIFE day center to socialize and receive health care services.The materials posted on the POGOe Web site are among the most frequently accessed on the entire site. For example, in November 2011 these materials received the highest number of hits for the site, which houses over 700 gero-focused curricular products.

This project is being accomplished with the help of doctoral and master’s level students at the Universities of Arkansas, Iowa, and Pennsylvania. One of these students is Lauren Massimo, MSN, CRNP, a doctoral student and a Hartford Foundation Building Academic Geriatric Nursing Capacity Scholar. Ms. Massimo became passionate about a career addressing mental health in older adults when she was a master’s degree student and wrote about depression in the older adult. “I realized that depression is frequently missed in the elderly, and there are higher rates of mortality and suicide as a consequence,” she says.

After receiving her master’s degree, Ms. Massimo co-taught a course on caring for the older adult to undergraduate nursing students at the University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing. “The care of older adults with mental health issues is very complex, and we did a good job of integrating it into our course curriculum,” she says, “but I think it could have been even better if we had had more resources.”

Dr. Pamela Z. Cacchione

Associate Professor of Geropsychiatric Nursing

University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing

Philadelphia, PA

“If I had these resources just a few years ago when I was teaching the course on caring for the older adult, I would have taught these very sensitive topics even more effectively,” says Ms. Massimo. By including these topics in the curriculum, nursing students like Ashley King will be better equipped to appropriately care for older adults with mental health issues like Roberto.

Endnotes

1. Gleason, O. C. (2003). Delirium. American Family Physician, 67(5),1027-1034.

2. Fick, D. M., Kolanowski, A. M., Waller, J. L., Inouye, S. K. (2005). Delirium superimposed on dementia in a community-dwelling managed care population: A 3-year retrospective study of occurrence, costs, and utilization. Journal of Gerontology. Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 60, 748-753.

3. Kurlowicz, L. H., Puentes, W. J., Evans, L. K., Spool, M. M., Ratcliffe, S. J. (2007). Graduate education in geropsychiatric nursing: findings from a national survey. Nursing Outlook, 55, 303-310.